This is an excerpt from Laleh Khadivi’s commencement address to the Reed College graduating class of 2016.

Once upon a time, on a May day, I turned in my thesis in a state of low-grade terror such that I heard absolutely nothing the commencement speakers said. In my semi-agitated state I could not be present. I was plagued by thoughts of tomorrow. The same tomorrow you have thought about these last days and months and that you may be thinking about right now.

The tomorrow that is your life.

I insisted on beginning immediately, a few days before graduation when I packed up my thesis desk, sold my bed and my very used car, and shipped everything else to my parents. The day after graduation, tomorrow, I took a one-way flight to New York City where I shared a room with a Reed grad. I had a fresh degree in political science, a non paying internship at human rights watch, an interest in film and politics and social justice. I had money saved from two years of tossing pizzas at a restaurant in northeast, which by naïve calculations, I was certain would get me through the summer.

There were a million reasons not to do this. You may have your own million reasons not to launch off in the direction of your wildest curiosity. Maybe you want to follow through on the academic momentum you generated, or you face the intense realities of the debt accrued in these college years and feel a strong pressure to act responsibly in the face of such great responsibility. For some of you it is the pressure of exhaustion. To put off life until you take a nice long break. It makes no difference, all of these scenarios eventually lead to beginnings of one kind or another.

I never considered my education at Reed job training, and decided, at this pivot to take what I had learned here as the equipment for adventure, the adventure of my first self made beginning. I told myself in the face of whatever obstacles I encountered I would remember to think with compassion and rigor, to consider an idea and its opposite without bias, to push beyond what I knew into what I wanted to know. I had no sense what this life would look like, I simply bought the ticket and was gone.

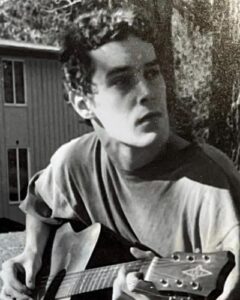

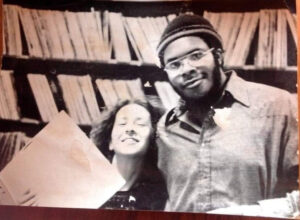

Going is in my blood. I am from going stock. Long before my mother father and I were refugees and eventually immigrants to the United States, my father came here as a very young man, on his own, in the early seventies. He did not come escape political persecution, as he would do in the years to come, he came because as a boy in Kermanshah, he went to the movies and watched the big wide world flicker on the screen and thought: I must go there. Fueled by imagination, a few dollars in his pockets and the phone number of a distant uncle, he arrived in Los Angeles and simply, began.

I think of him often when I read and write of the men, women and families from the Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria who, for their safety and survival, are forced to imagine and pursue a new life. As we have all watched these last months and years their journeys tracked on ariel maps and front pages, my thoughts always go backward to the moment they closed the doors of their homes behind them for the last time and began to move in the direction of the un-tested life, the first and second and third steps in a long and difficult beginning, and I am reminded that beginning is a heroic act, no different than Dante descending behind Virgil into the underworld or Odysseus’s determined trek back home. There is a profound bravery in beginning, born of the willingness not to know your own fate.

I arrived in Rudolph Giuliani’s New York City where I knew no one except the former Reedie who woke me up every morning by ironing the wig she wore to the job that did not take to kindly to her shaved head. Our two rooms, living room and bedroom, were small for four girls, and on some mornings the block’s homeless family choose our curb as their outhouse, but who cared? Everyday I woke up and went to work on the 54th floor of the Empire State Building to answer the phone calls of men and women in various states of exile and persecution and worked as an assistant at their film festival, my job being to escort filmmakers fresh off planes from St. Petersburg and Bombay to their hotels, listen as they told wild stories and sit quietly as they rode in silence through the iron valleys of Manhattan. I was enchanted. At night I worked as a waitress in a café where drunk tourists regularly threw up in the cappuccinos I served them. I was mugged, twice. I went to incredible free concerts in Prospect Park. I took extra work as a house cleaner. I rode my bike everywhere all the time. Though I didn’t know it at the time, I was finding my passion What they don’t tell you in these speeches is that passion is a rough diamond, and you must spend many moments deep in the mines of some job or cause that is the opposite of your passion, toiling away, bumbling around, until the glittering speck is revealed.

Eventually I interviewed with a filmmaker looking to hire a grassroots media activist. I convinced him I was a grassroots media activist and soon I was working in film and social justice and when the filmmaker wanted to make a film about Louisiana’s largest prison for women. I convinced him I was a filmmaker and oddly, he believed me. With some trepidation and much excitement I began again.

Do not believe that beginnings are a smooth ride.

It was inevitable that my bravado and hubris would catch up with me. On the night before my first shoot I locked myself in the bathroom of my tiny hotel room in St. Gabriel Louisiana, and called my mother to admit fear. I had no idea how to lead a crew, what questions to ask woman who had served five, ten, twenty years and my mother listened as I sobbed onto the peach tile floor. Oh Laleh she said, It is ok. You did not have this job six months ago and you were fine. What difference does it make if you do not have it tomorrow? There is always med school.

Though she might have had ulterior motives, her advice relaxed me. My mother’s words gave me the permission to fail. And that in turn gave me courage beyond courage.

I realize this is a cliché of the commencement genre, but I will repeat it: you must fail spectacularly. I made many mistakes on that film. I asked serious woman stupid questions. I lost four days of footage when my checked baggage was stolen. I cried in front of Antoinette Frank, Louisiana’s only woman on death row. But failure has a glory unto itself. Because in the end, regardless of weather you fail or succeed the dust of your bones will be the same. Dusty. Try not to envision the trajectory of life as a long straight line rising smoothly at a 45-degree angle. Much meaningful progress comes only after stumbling and stalling and if you can, you should make your stumbles bold and worthy and at the very least, a little fun.

For four years I worked as a filmmaker and producer. In this time I spoke to men and women caught in the wires of this country’s deeply flawed criminal justice system. These citizens trusted me with their stories and I did my best to broadcast them, realizing as the years passed, story is the only thing that binds us. Time and time again I’d sit across from an inmate, the two of us strangers, and by the end of their stories we knew each other, a membrane broke and something was shared. When I sat where you sit now, I did not know this, about stories, about strangers. This truth was a result of a beginning that felt, at the time, both fearless and foolish.

It does not matter where you begin. What matters is that you, with good intention, begin. And that you know where to end. After four years I could not chronicle the life of another woman who had lost custody of her children or another man in prison hospice. My youthful impatience made it seem as if broadcasting these stories had little significance on policy or even reality and I sought out work that garnered greater and more immediate effect. I left film and began again, as a writing teacher at Rikers Island. I guided students through self-expression and though the results did not reach into the living rooms of America, they reached inward into their hearts and minds of the writers and audience and left and the intimate effect resounded. There was always a disgruntled student who took pleasure in questioning my authority and asked: are you a writer? To which I had to respond: no. I felt myself approach another beginning. I could see it out on the horizon.

Just before September 11 I moved to San Francisco, where I worked as a waitress in the depressed post dotcom city. I continued teaching in prisons and now a complete believer in the power of story, began writing my own work. I took a few writing classes, got mixed and occasionally terrible feedback but continued on, as beginnings have their own energy and the engine of the story stayed hot beneath me. Eventually I rode it all the way through an MFA and the completion of that first book, which gave me entry into the trilogy ten years in the making, now near finished, that I was working on when I received the invitation to speak at today’s ceremony.

Interestingly, I was drafting a commencement scene. The protagonist Rez, a surfer stoner born to Iranian parents, but otherwise wholly American is about to graduate from his Laguna Beach high school. The book is a somewhat dark chronicle but in the graduation scene Rez has just taken mushrooms and sits down to listen to the high school principal give his address. Ok I thought while writing, I’ll get him in a little high and then put up the dorky principal for a dorky speech no one wants to hear. Could be funny. Little did I know life would imitate art. In any case I’d like to read you a bit of what I wrote, as it spontaneously mentions Ovid and Ovid was one of my favorite things about Reed. The principal begins.

The meaning of ceremony is to denote a moment of significance. To bring together family and friends to recognize a transformation. In his timeless collection Metamorphosis, the Greek poet Ovid reminds us…everything changes nothing is extinguished.