By Richard Panek

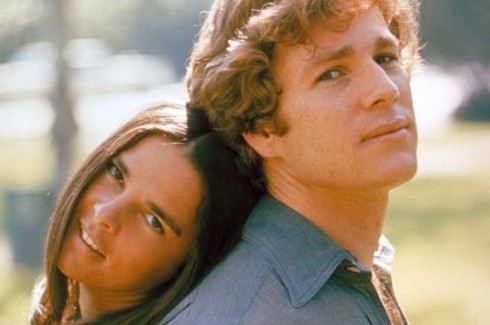

Two years ago I wrote an essay for another website, lastwordonnothing.com, that I called “Love Story,” and for the opening I paraphrased the opening of the novel of the same name:

“What can you say about a fifty-seven-year-old book that has outlived its usefulness? That it was beautiful. And brilliant. And taking up valuable space in my personal library.”

Back then, the problem was that I was running out of room to work. Our apartment has six 84-inch-tall bookshelves lining two living room walls, and four more in the bedroom. All of the living room bookshelves and two of the bedroom bookshelves hold the kinds of general reading that line the living room and bedroom walls of most households that still bother with books: novels, nonfiction, poetry, plays, reference works. But two of the bedroom bookshelves, the ones flanking my desk, hold volumes that are not the kind you typically find in a home, unless one of the people who live there happens to be someone who writes about science.

These were books I had accumulated over many years in the course of conducting sometimes obscure research. Now I was starting a new project that would require the accumulation of new research, but I would have no place to put it. The obvious solution, I knew, was to get rid of the old research first.

Those books, however, were not the kind that anybody would want. Many were discards from personal collections or public libraries—the type of online purchase where the shipping cost is higher than the price. I could give them to charity, but what bookselling non-profit would want to waste shelf space on a product that nobody would buy? I could throw them away, but these were books. You don’t just throw away books. Well, maybe you do the classics dating back to high school or college, if you have duplicate, coverless paperbacks of The Catcher in the Rye or Jane Eyre. But what about titles that are on the verge of extinction? Toss a coffee-stained The Unbearable Lightness of Being down a trash chute, and there will still be millions more out there. Do the same to a collection of the Hixon Lectures as delivered at the California Institute of Technology’s Department of Biology between March and May 1950, and civilization dies a little.

So I kept them. By day I resigned myself to writing at a desk that was losing the battle with entropy. Then I abandoned my “office” altogether to write at the desk in the bedroom of my older son, away at college. Then, when the accumulation of books there also defeated me, I moved my office to the living room sofa.

By night, though, I returned to the bedroom. There, lying on my left side, I would eye the books on and under and around my desk with growing dispassion. Increasingly I felt I could see them as they really were. Unblinded by love, I discovered—just as Robert Grimm had, long after he signed his name and the date 1960 in this book over here, or just as the Mary D. Reiss Library of the Loyola Seminary in Shrub Oak, N.Y., had, long after an anonymous clerk inscribed “BF 173 .N44 1958 c. 2” in white ink on the black spine of that book over there—that I could live without them.

Still I kept them. Because, you know, books.

This fall, though, my wife and I are moving. We simply won’t have room for—or want—ten bookshelves. (Eleven, if you count the books sitting on, under, and around what used to be my desk.) (Well, twelve, if you count the books sitting on, under, or around what used to be my older son’s desk.) (Okay: thirteen, if you count the books sitting on, under, or around the coffee table in the living room.)

I must say, my wife and I have been admirably merciless. Box after box after box we’ve filled with books from the living room shelves—books in perfectly good condition, but books we haven’t looked at in years, decades even, books we know we will never open again. Awww, we’ve gone, again and again, exchanging pained expressions, before tossing a ’60s mass-market best-seller or ’70s small-press chapbook or ’80s short-story youthquake collection.

The separation from my own books, though, I conducted privately. After all our time together, I felt they deserved that consideration. I waited until my wife was out of the house—out of town, actually. In the bedroom one morning, the books and I were alone. I looked them in the eye.

“It’s not your fault,” I told them. “It’s mine. But…I need my space.”

By the time I called Housing Works, an AIDS charity in New York that runs a bookshop in SoHo, my wife and I had 23 boxes to donate. They said they’d send two guys and a truck. A few days later I watched from my apartment doorway as the boxes were wheeled down the hall to the elevator, there to vanish from my life forever, and maybe to enter another’s. Or not. It would be on Housing Works’s conscience now, what becomes of one of the few remaining copies of the 1950 Hixon Lectures. As for me, I can only paraphrase Erich Segal, whose most popular novel will always have millions in print, no matter how many paperback copies of it we might toss down trash chutes: Donating a book to charity means never having to say you’re sorry.