There is something rotten in Denmark: transforming life, scholarship, and writing toward a more sustainable paradigm —or —you’ve got the craft skills, now what are you going to do with it?

There is something rotten in Denmark: transforming life, scholarship, and writing toward a more sustainable paradigm —or —you’ve got the craft skills, now what are you going to do with it?

By Karen Walasek

Anyone alive who is paying attention knows that we are on a crash course toward climate destruction and that the burning of fossil fuels is the key culprit. Any writer who is paying attention to the adjunct market post 2008 meltdown has noticed that adjuncts are not paid a living wage. There are a great many articles on the extractive crushing of the creative class, the war on education, non-whites, women and the environment. Our food is literally killing us as the militarized mindset of ever increasing pesticide use (let’s kill off the bad guys with bigger and bigger guns) is touted as the only way it can be done, but says who? Writers, of course. We are the ones making the culture, but do we take our role seriously enough? Have you thought about it? In what ways does your writing support or enable the paradigms of destruction that are racing us closer and closer to the tipping points of planetary collapse?

When I left Goddard with my MFA certificate in hand granting me all the rights and privileges associated with that degree, I had the gnawing sense that there was something rotten in Denmark. No offense to my Goddard colleagues, professors or even Shakespeare, but it bothered me that one could craft a beautifully articulated blueprint for a dying planet that could be considered a literary masterpiece that left its readers filled with remorse and hopelessness. It is as if in our esteemed postmodern world we were all subjects of some grand cultural machine that we inevitably had no control over. The only thing that mattered to this machine was how expertly we crafted our sentences while passively describing the rising waters of Anthropocene’s doom and gloom. Oops, stop! You used a cliché. You don’t want to use a cliché, that’s blasphemy! And yet the paradigms that promote a dying planet are not blasphemous? How did we get here and do we know what we are doing? Pardon me for drawing unsubstantiated conclusions, but something tells me there’s a disconnect in the mind of writers that has a heavy sprinkling of denial, and it’s not that we are creative dreamers and have our heads in the sky. It’s something far deeper and darker than that. Who among the numerous MFA programs out are there are talking about the responsibility of the writer in promoting social change?

What about that doom and gloom, no-way-out scenario? Is there something disingenuous and inherently passive in those action scenarios that promote a survival of the fittest paradigm, only to pull a bad sarcastic cosmic joke in the end with a “Guess what! Nobody is fittest, nor a hero, and we all die; hearty har, har.” And we call that believable, realistic, or noteworthy, while anything that falls outside this paradigm is Pollyanna, Mary Sue; or heavens forbid, idealistic or romantic chick lit!

In his book, Metaphors We Live By, George Lakoff makes the point that the words and metaphors we choose shape how we think. My first stop post Goddard was a M.Ed. in education at Portland State University where I dabbled in rhetoric, conflict resolution, sustainability and indigenous nation’s studies. It was here that I also came across the work of LeAnn Bell in a Storytelling for Social Change class. Bell used storytelling as a tool for addressing racism. She categorized stories as dominant, concealed, resistance, and emerging (or transformative). Most of the stories in popular Western culture fall into the dominant story category. They tell us that those wolves on Wall Street control the world and that our planet is dying and we are helpless to do anything about it. They are the ones that say money is the only thing anyone cares about and life is nothing more than a complicated a con game. If we want to follow the plot twists, all we have to do is follow the money. The concealed stories, of course, if I dare get political here in my professional essay, the concealed stories include those like the ones that Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders are telling. The concealed story is the one that David Graeber tells in his book, Debt the First Five Thousand Years, where he reveals how monetary debt and true obligation are NOT the same thing. The resistance stories include those of Black Lives Matters or the ones about that tribe of brave indigenous people in Brazil who are literally fighting for their lives to stop the Bela Monte dam. (http://amazonwatch.org/work/belo-monte-dam)

I think as a writer the most important question I can ask myself is “Whose story am I telling?” Do I really want to tell a story that leaves my readers hopeless (so I can sit back and feel good about how cleaver I am) or do I want to tell a different kind of story? Did you hear the one about the farmer who doesn’t till his soil in California and uses less water than even his organic counterparts? I met him at the recent Soil Not Oil Conference where he explained how his version of small agriculture puts the carbon back in the ground! (http://craftsmanship.net/drought-fighters/)

Holy shit, does that mean if we altered the way we farmed our food, we could avoid climate change? Why aren’t more writers telling stories using this kind of narrative? Why don’t we draw from them to write our poems, our fiction, our movies?

Since I got my MFA I’ve been searching and studying. I felt like I needed to do my homework to look outside of my insulated world of being a writer in the United States. I fell in love with the work of Vandana Shiva who had the most pragmatic understanding of human rights around agricultural and trade agreements that I’ve read to date. Yes, it is true I will admit clichés (are lazy and ineffective and as such) don’t belong in our literary work, but don’t we need to also ask the important cultural human questions alongside the craft ones? What is your story saying to people? How does it shape the writer or the reader? Does it inspire? Does it help us in any way to find our way out of this mess we are in? Is it making the true bad guys heroes? What alternatives to climate collapse am I supporting or not supporting? Do I know what reductionist thinking is? How might my plot structure promote mechanistic thinking? What did Ayn Rand do that might have fueled a generation of narcissists? How does my world view influence my work? Whose story is it and is this a story that needs to be told? How does my story help the world become a better place to live?

When I became a writer in the world, I couldn’t stop asking myself these kinds of questions. My writing needed to do something good. I say this understanding all the banal realities of a now struggling Ph.D. student who barely pays my rent on time every month, knowing full well that in some countries this would be considered barbaric. I fear for the world my grandchildren will live in, if they survive at all. I’m outraged every time I hear that some ignorant fool has shot an endangered animal for a trophy; and that Obama actually gave Shell Oil permission to drill in the artic; perhaps thinking the restoring of a mountain’s name to its indigenous roots would make us all feel better about the drilling. Yes, I have my moments of vanquish, but in spite of this, I have come to know my biggest job is to have hope and to write to that hope. To do otherwise would just make me a part of that dominant paradigm, the one that thinks we have no choice, and I know better. I have seen the alternatives. They are endless in their variation. The long descent into annihilation is not the only story to tell. Ron and I were honored to teach a workshop on writing for social activists at the above, Soil Not Oil conference. Among the participants were fledgling writers and poet laureates. All were inspired, all were fueled by the passion to have their work make a change in the world, and so I ask my literary colleagues, want to join us? What else are you doing with those nicely honed writing skills?

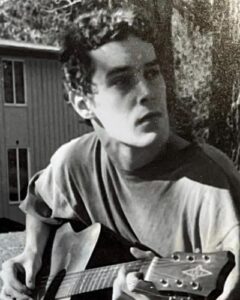

Karen Walasek, MFA, M.Ed. is a Ph.D. candidate of sustainability education at Prescott College. Her photo was taken by Ron Heacock.